With some aggressive training rides and some racing on my new Ritchey Swiss Cross I can offer some informed feedback.

The bike has classic lines and simple panel paint scheme consistent with its heritage as a race bike. Several companies offer steel cross bikes, but few outside of boutique builders Zanconato, Vanilla and Richard Sachs offer a true steel race bike.

I hadn’t ridden a cross bike since last year’s Gravel Grinder but I have to say the Ritchey handles more like a mountain bike than any other cross bike I’ve ridden. Switching over to this felt very natural and predictable, which shouldn’t be a surprise given Ritchey’s experience building cross bikes for mountain bike racers.

There’s still a skinnier-tire learning curve after spending so much time on fat tires, but the Swiss Cross is a great blend of smooth ride feel and predictable handling. My first impression was how well the bike matched my expectations right out of the box. The overall fit and layout is overwhelmingly race-oriented, but the good news is that for a ‘cross bike that still means an upright and comfortable position relative to a purebred road machine.

The steel frame and all carbon fork work well together to smooth out trail chatter and provide a consistent feel front-to-back. Ride quality is exactly what you’d expect from a steel bike: smooth and stable without being too flexy. Although the bike takes the edge off of rough terrain it’s by no means springy or wallowy, and vicious pedal strokes are converted directly to forward movement.

Fans of steel will be well familiar with the amazing ride feel of bikes like the Swiss Cross. I describe it as a subtle version of the short travel full suspension/hardtail contrast- there’s a slight weight penalty, but the additional compliance means more consistent power output and a smoother ride. Like mountain bike races, ‘cross events are contested on off road courses so it’s not just about having the lightest or stiffest bike; handling and ride quality also need to be factored in when selecting equipment.

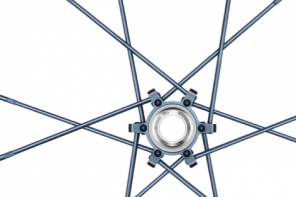

One of the updates from the original 90’s version is the integrated bearing cups. It’s a small thing that adds a modern touch and saves some weight in the process.

There’s no frame mounted barrel adjuster for the front derailleur so you need to run one in-line.

Fortunately this frame is devoid of rack and fender mounts but does have bottle mounts. You can easily use the stock bottle bolts to fill the mounting holes but I prefer to use nylon bolts cut to length. They cost about $.70 each at the hardware store and not only do a great job of sealing out moisture but also look really pro.

The rear brake routing uses a straw-style cable guide around the seat cluster. This was common with steel bikes and is similar to the sleeves used in internal cable routing. I used a short length of rubber hose from a nosed cable ferrule, but really any sturdy small diameter tubing (like heat shrink tubing) would work.

The Swiss Cross uses a modern 27.2 seatpost unlike many of its steel predecessors that used a 26.8 or 27.0. The thin diameter triple butted seat tube uses a relatively rare 28.6 front derailleur clamp so if you’re using a SRAM drivetrain you’ll need to use a braze-on front derailleur and source the clamp from Shimano or Problem Solvers since SRAM only offers front derailleurs in the more common 31.8 and 34.9 sizes.

Ritchey socket dropouts were the standard for high quality production steel bikes. Like most steel frames the derailleur hanger is dedicated and can be worked back into position rather than replaced.